The Art of Building Offense

Anybody can construct an offense. It only takes an empty playbook and a pen to draw plays and write down assignments. Unfortunately, if that were all it took to successfully outmaneuver opponents, many of us would have been real offensive coordinators on the backs of our homework assignments in 10th-grade Math, or will be real offensive coordinators in our custom NCAA 24 playbooks this July. The art of offensive architecture lies not really in the design of plays, but in the design of systems. Systems contain plays, but are ultimately defined by their ability to do the following.

1: Establish core principles. Building around your talent is key, the bedrock of your offense should fit together and weaponize the strengths of the players on the field.

2: Build variation off of these core principles. Like in pitching, your sliders and changeups should be rooted around your fastball to keep opponents off-balance.

3: Answer the answers. That variation needs to exploit the weaknesses of what opponents do to take away your core principles. For instance, if a team cheats safeties down to answer a heavy run game, throw over their head from the same formations off of play-action to punish it.

4: Marry every element of the offense. Every element of your offense, whether it be inside run and outside run, play-action pass and RPO, run game and movement (boots and rollouts for the QB), run game and play-action, needs to link together so that your offense runs like a machine instead of a scattered assortment of bolts and wires.

These requirements aren’t unique to football. After the 2nd of back-to-back National Championships, UConn Men’s Basketball (not Los Angeles Lakers) Head Coach Dan Hurley sat down with possible Lakers head coach JJ Reddick to discuss how he and vaunted assistant Luke Murray constructed their offense, which has become the talk of basketball analysts everywhere, the way the Shanahan offense has in the world of football. He discussed how they built a system, and how they sequence their key concepts with changeups to make themselves un-answerable.

I encourage you to take 3 minutes and listen to Uconn Head Coach Dan Hurley describe how he and his staff built the Huskie offense.

You rarely hear a head coach go into such incredible detail.

Shoutout @jj_redick for prompting the answer.

Basketball bliss. pic.twitter.com/dXs6HhCyOp

— DJ (@DJAceNBA) April 19, 2024

In football, it is key to have a set of plays that constitute your “anytime calls,” which are concepts you feel comfortable calling no matter what the defense is doing. These plays usually have multiple options built into the play that provide different answers to almost anything. The more you get out of your anytime calls, the easier it is to call plays.

Spread offenses like LSU’s allow for more routes to be put on the field, and when fit together properly, each route can give you that different answer. As Mike Leach said:

The brilliance of LSU’s offense last year stems from its simple complexity, which can be exemplified by its favorite pass concept, popularly known as “Shock.”

Base Concept

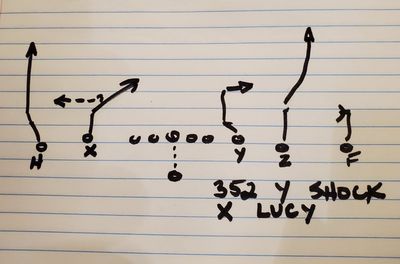

A staple of NFL passing games, the concept is most associated with the Brees/Payton era Saints as one of their best calls out of empty, though it can be run from any formation with 3 receivers to a side. The relevant concept below is pictured on the 3-receiver side (paired with a backside choice, or “lookie (called Lucy in this formation)” route by the X).

@SeanPayton, Twitter

Shock consists of:

-Stick route by the number 3 receiver (inside-most receiver in trips often the TE, or Y, but not always),

-Slot fade

-Shallow hitch by the number 1 receiver.

As outlined below, even the base framework gives you answers to a lot of different coverages.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

The outside hitch is good against anything where the corners play off the line, like Cover-3.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

The stick is good against most quarters looks (with some exceptions where the route is jumped). Auburn is playing a bracket, so the slot defender is run off altogether, but often he is responsible for the flat and widens outside of where the stick route usually hits.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

Against tight coverage with limited safety help, such as Cover-1 or many blitz situations, the QB always has the option to take the slot fade for a big play if he likes it.

Pairings and Variations

So now that the foundation is set, how does the rest of the building come together? The only thing required to run this play is a 3 receiver surface, so it can be run from a bunch of different formations, with a bunch of different things tagged to the backside of the formation. LSU had around a dozen different tags on the base concept, touching every part of the offense from the pass game to the run game. Below are just a few, but there were more.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

Here is the standard Shock/Lucy. The slot-choice route attacks the backside if the Mike LB (here over the TE) pushes frontside to relate to the stick from the 3 receiver. This creates a 2-way go against the last guy, either the WILL LB or in this case, the collapsing Safety, to the backside. The receiver just breaks against that defender’s leverage, making him wrong.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

A “basic” (intermediate in-breaking route) tagged to the backside presents a similar idea. If the 2nd level defenders push to the strongside, the basic attacks the vacated area behind them.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

If you expect man coverage, an isolated go by the backside receiver (X receiver) can be tagged to used to attack vertically. The idea is to force the middle-field safety (known in coverage terms as the post safety) to choose which he leaves 1 on 1 between the slot-fade inherent to Shock, and the backside go. If he stays deep middle like he does here instead of shading over to help on time, they’re both 1 on 1. This is a good way to weaponize elite receiving talent.

RPO Integration

Because LSU presents the concept so frequently from 3 receiver formations, packaging it into the RPO world opened up the run game by tricking and conflicting 2nd level defenders.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

Here it is paired with standard inside zone. I don’t think I saw a single time where LSU threw the ball, so it’s mostly done to open the run game, but I’d imagine the QB has the option to throw if he likes it.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) May 15, 2024

The play was used a lot to open up the QB run game. The idea is to space out the 2nd level defenders and open rush lanes inside. The MIKE’s coverage responsibility on the stick route takes him out of the play, isolating the WILL in the box for the uncovered lineman to climb to, with the RB taking the MIKE as he adds late support.

— MTFilmClips (@MTFilm) June 10, 2024

The same idea here out of empty. Watch the MIKE turn away from the core. He’s in a lot of horizontal conflict, responsible for both the A gap in run defense and relating to the 3-receiver in coverage. By the time the nickel alerts him to the draw, it’s too late for him to play his gap.

Conclusion

It’s the illusion of complexity. You can force defenses into irreconcilable conflict without doing too much if you know how to serialize your offense. If you don’t have to do a lot, you can maximize execution, help your players play instinctually and fast, and master your fastball. Some offenses, like the Heupel/Briles deep-choice “veer and shoot” and the triple option take this to truly extreme levels. The more efficient you are at layering on top of the foundation, the less you have to sacrifice those benefits to keep defenses off balance.